Syrian Story

Hello, my name is Rana. My family is originally from the southwest of Syria in a city called Daraa, it is located about 13 kilometres north of the border with Jordan – I lived in Damascus for some time – I was a teenager before I left my beloved Syria approximately a year before the conflicts started.

The story I will share is not entirely mine but more about my uncle Bashar. Although we do not have a huge amount of contact now that is not for any particular reason other than my uncle’s knowledge and understanding of technology.

Bashar married Khetam about 10 years ago, his 2 kids live with him now in Sweden too. Mohammad is the older boy and Sami is the other.

In Syria, the conflict started in Daraa, as a direct result my family had to move to Damascus as it was seen as the safest location in Syria at the time. They moved from Daraa to Damascus mid 2011.

How it all started was with radicals and demonstrations. Over time it then moved to full blown conflict. To give you a sense of why my family moved, like so many, was because of the experience of lack of electricity and water – gas bottles weren’t available which was traditionally used primarily for cooking – there was a lack of diesel for generators too – food was scarce. In those times it was not as dangerous as Aleppo though shells and bombs being dropped, which seemed random. There were shootings and snipers which were an everyday occurrence. I was lucky to go to study in Russia. At times, I wonder if a guardian angel pushed me to move elsewhere at the time, I did so I didn’t personally witness or experience the worst of it directly.

Our family’s apartment was destroyed even in Damascus. I recall my aunt disappearing at one point…. A few days later she reappeared – my family certainly experienced forced migration in our own country.

My family is from a humble background. Not a huge amount of money. The rich Syrians were able to leave – however my family didn’t have that privilege.

Now to share more about my uncle’s experience. He had to make a choice of what was the best course of action to take, for both himself and his young family. He felt he did not really have a choice so was forced to migrate also. The options were not very many but he determined not to go to Lebanon but instead went to Jordan –At that time, the Lebanese seemed to be scared that the Syrians would take jobs etc. so they felt very unwelcome there.

Bashar left his wife and 2 young boys to go to Jordan to explore options in 2011. No jobs so no money or income was coming in so the country was upside down and inside out…. There were vouchers for food but no real future from his perspective. In Jordan, he paid a smuggler with what money he could get together and went to Turkey.

He did find a few jobs but wanted to go to Europe as he felt he would have better prospects there and so went on a boat to Athens – there were so many refugees there also – he and the men he travelled with found themselves living in small tents. The majority of refugees in Greece experienced lack of safety due to stealing and physical violence, this was not how he could choose to live and so they considered what could be next though they stayed there in the camps for about 2 months.

There were 4 of them traveling together, one of their great difficulties other than the basics of food and shelter was to stay in contact with his family. They found that the lines for refugees is too long, surrounded by insecurity they decided to walk through the border through Macedonia with the understanding that in Sweden they accept you as a refugee with the production of a Syrian passport.

They walked during the night, through mountain hills, one of his friends fell down a cliff – they had to choose to leave him there or go find him and potentially not make it themselves. They chose to leave and to this day they do not know his fate. They did whatever was necessary to find food along the way as they did not have the option of shopping for their basic needs – From my perspective I feel that Bashar still has a sense of shame around what was needed to be done to survive. The walk took about 3 weeks in total; once they were in the EU they were able to move relatively freely due to EU law.

On his arrival in Sweden he handed over his passport – he was in a room with a number of others – he got refugee status reasonably quickly which included support from the government – he was required to get training of some sort to secure payments so he was trained to garden. After more time he was able to secure safe passage for his wife and children. In Sweden you have to contribute to be able to get the payment from them – they all received Swedish classes and can all speak Swedish now.

He started his journey in 2011 and is still working his life out… If it wasn’t for the war his kids would have been nearing high school, they would have never left home and travelled that far leaving everything behind.

Syrian forced migration causes & statistics (to be added to the Syrian page as additional information after the Video and the transcription)

According to World Bank data prior to the civil war, Syria had a population of just above 21 million people. This rate of civilian displacement in a civil war may be unprecedented in post-1945 history.

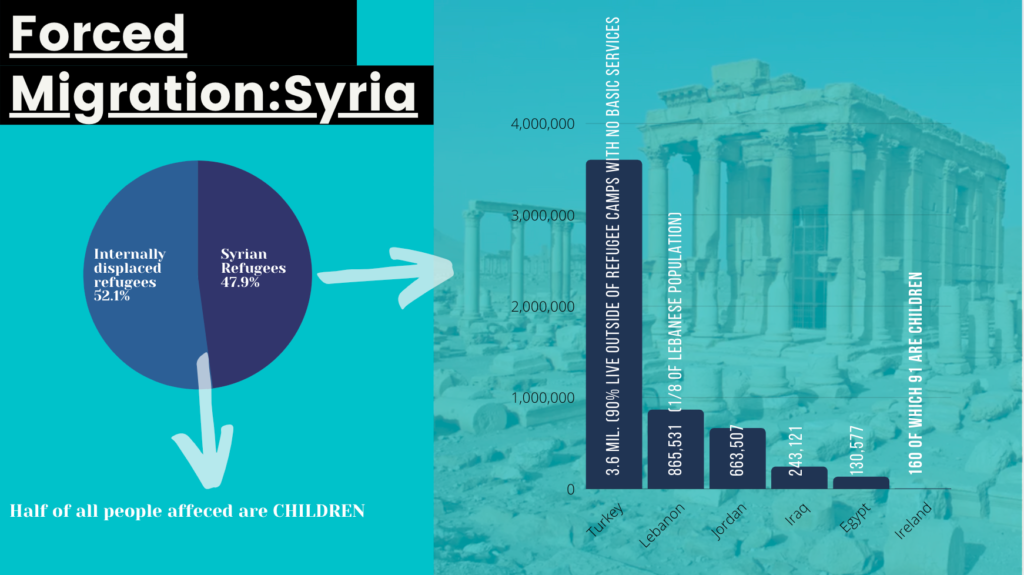

There are about 5.6 million Syrian refugees, with an additional 6.1 million people displaced within Syria. At least 11.1 million people in Syria need humanitarian assistance. About half of the people affected by the Syrian refugee crisis are children. Please keep in mind that the population of Ireland is a little under 5 million as of 2020.

Reasons:

Violence: Since the Syrian civil war began, nearly 585,000 people have been killed (that’s the equivalent of over 2 times all the people in Cork City with a population of 210,853 people in 2020), including more than 21,900 children, reports the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. The war has become deadlier since foreign powers joined the conflict.

Collapsed infrastructure: Within Syria, only 53% of hospitals and 51% of healthcare facilities are fully functional, and more than 8 million people lack access to safe water. An estimated 2.4 million children are out of school. Conflict has shattered the economy, and more than 80% of the population lives in poverty.

Children in danger and distress: The hope for a better future are the Syrian children, They have lost loved ones, suffered injuries, missed out on years of schooling, and experienced directly or witnessed unspeakable violence and brutality.

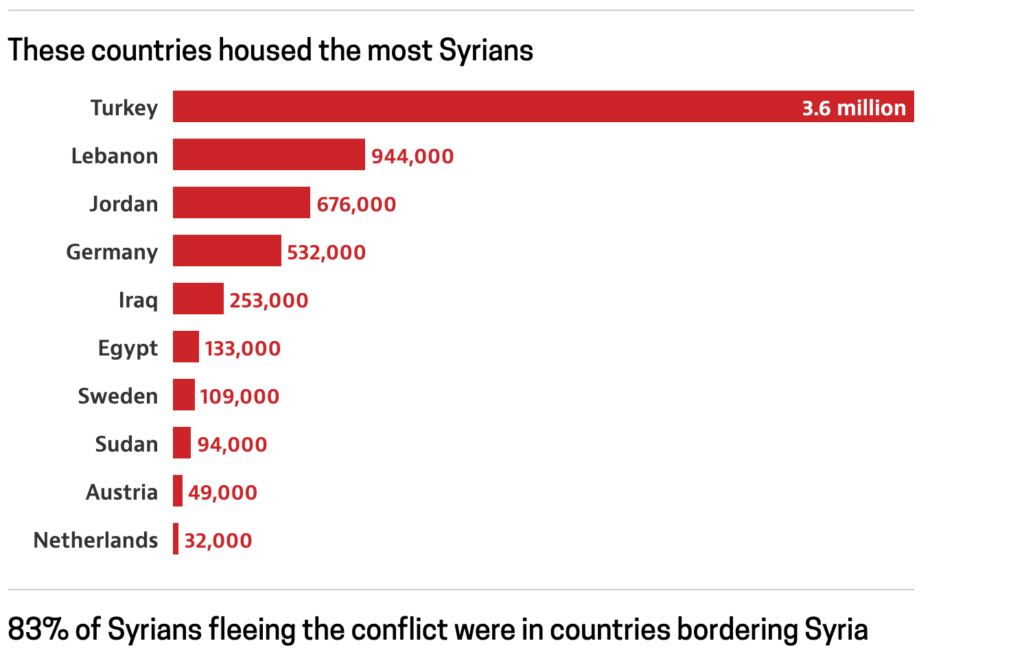

Where are Syrian refugees going?

In 2018, 6.7 million Syrians were in other countries after fleeing the conflict

By land and sea, the majority of Syria’s 5.6 million refugees have fled across borders to other Middle Eastern countries. Some examples of these follow:

Turkey — 3.6 million. About 10% of Syrian refugees in Turkey live inside refugee camps and have limited access to basic services.

Lebanon — 944,000. Syrian refugees make up about one-eighth of Lebanon’s population. So may survive in primitive conditions in unrecognised refugee camps that are made up of informal tented settlements. Basic human needs such as rent, utilities and food are difficult rare legal income opportunities.

Jordan — 676,000. Some 120,000 people live in converted desert wastes into cities (Za’atari and Azraq refugee camps).

Iraq — 253,000. Most are integrated into communities putting strain on services. Many in areas where more than 1 million Iraqis escaped ISIS from the northern Kurdistan region.

Egypt — 133,000.

Sweden – Where Bashar and his family now live is 109,000.

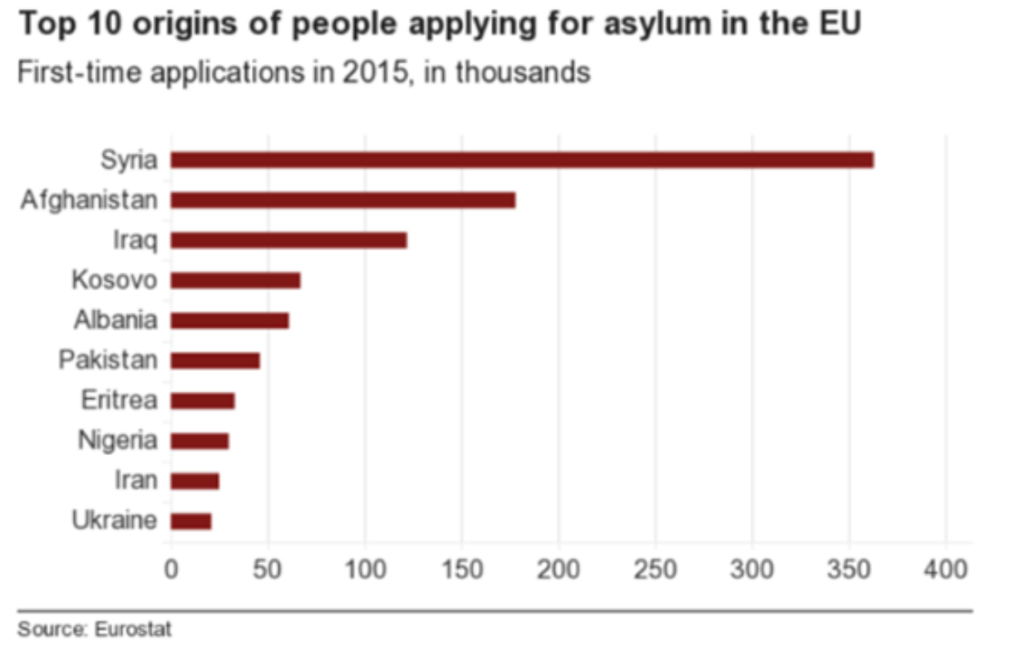

In 2015 at the height of the European migrant crisis, 1.3 million Syrians sought asylum in Europe. Since then the number of new asylum seekers has declined. 160 Syrians (91 are children, arrived in Ireland under a State protection programme.

The United States admitted 18,000 Syrian refugees between October 2011 and December 31, 2016.

The following gives a sense of the number of people seeking asylum in the EU in 2015.

Looking forward about what’s next (Development and Education):

Millions of Syrians spend the last number of years trying to create a new life outside of Syria. Unfortunately many of them will never have the opportunity to return to their country of birth. Those who do go back, maybe because of a particularly powerful emotive link to their homeland, or because the location they have found elsewhere is dismal they have the prospect of joining several million internally relocated people who also have to determine where and how to recreate their environment. Past experience suggests that they will probably stay in sizable and expanding cities. One of the imperative policy implications of this argument is that as the international community initialises a post-war rebuilding of Syria, all stakeholders should focus on the major municipalities and anticipate displaced people to collect there. Rebuilding cities involves creating the environments for a vigorous private sector to produce financial expansion. Specifics such as the planning of housing and transportation policy with the understanding that the original population will increase after the war comes to an end. As we consider countries in the west, we have limited capacity to recreate rural regions in any structural economic decline, or to undo out-migration that usually describes such areas. In Syria, it would be foolishness to pursue this impractical mission, and unwise, it could potentially be outright dangerous if we do not support Syria, when the time comes to prepare for its growing cities that will bring together vast numbers of new residents.